Focus | Saab reveals sixth-generation manned and unmanned fighter concepts for Swedish Armed Forces

{loadposition bannertop}

{loadposition sidebarpub}

On August 24, 2024, in an interview with Dagens Nyheter, Peter Nilsson, Saab’s Head of Advanced Programs, announced that Saab is advancing its development of both manned and unmanned fighter concepts as part of efforts to establish a sixth-generation combat air platform for the Swedish Armed Forces. Nilsson provided details on Saab’s ongoing exploration of future fighter options on behalf of the Swedish government, presenting the company as a candidate for developing Sweden’s next combat aircraft.Follow Army Recognition on Google News at this link

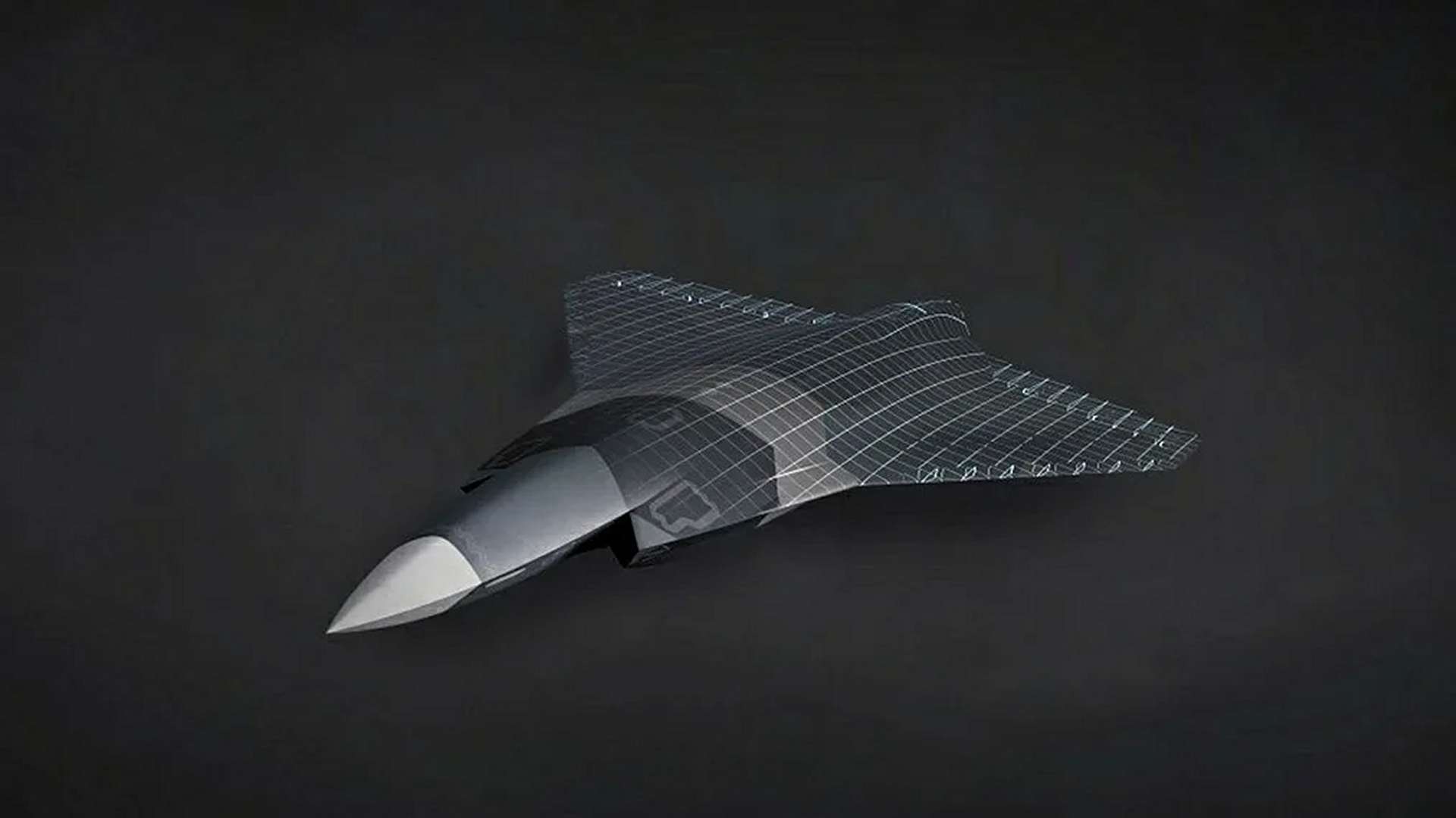

Saab is working on both manned and unmanned fighters as part of efforts to establish a sixth-generation combat air platform for the Swedish Armed Forces. (Picture source: Saab)

Nilsson argued that conditions are currently favorable for Saab to build a new combat aircraft for Sweden, citing the availability of a trained workforce, the use of modern digital engineering techniques, and experience gained from recent projects such as the Gripen E fighter, the GlobalEye surveillance aircraft, and the T-7A trainer aircraft. He addressed concerns about the costs associated with developing a new fighter aircraft domestically, suggesting that these concerns may be misplaced. He referenced the development of the JAS 39 Gripen in the 1980s, when similar doubts were raised but ultimately overcome.

Sweden’s development of turbojet-powered combat aircraft began with the Saab 21R, a jet adaptation of the earlier piston-engine Saab 21, which first flew in 1947 as Sweden’s initial jet aircraft. This was succeeded by the Saab 29 Tunnan in the early 1950s, featuring a swept-wing design and capable of achieving supersonic speed in a shallow dive. The Saab 32 Lansen, which entered service in the mid-1950s, was designed for various roles, including attack, reconnaissance, and maritime patrol.

The Saab 35 Draken, operational from 1960, utilized a double-delta wing design and incorporated canard foreplanes to enhance performance. The Saab 37 Viggen, introduced in the early 1970s, included modern avionics, an afterburning engine, and a thrust-reversing capability, supporting both air defense and ground attack functions. This progression led to the Saab JAS 39 Gripen, which entered service in the 1990s as a multirole fighter with updated avionics, fly-by-wire controls, and a modular structure designed to fulfill various military roles.

The Saab 29 Tunnan was launched in the early 1950s as the first post-WWII Western European fighter to be produced with a swept-wing design. (Picture source: Flickr/Ragnhild & Neil Crawford)

Nilsson suggested that a similar approach to the development of the Gripen could be effective for a new fighter aircraft. This strategy involved collaborating with multiple international partners while maintaining control over the design process within Sweden. He noted that the Gripen E, while primarily developed by Saab, includes a significant proportion of components from foreign suppliers, with Saab integrating these into a single system. This model could potentially be applied to future projects, balancing local oversight with international collaboration.

As part of these efforts, the Swedish Defence Materiel Administration (FMV) signed a contract earlier this year with Saab and GKN Aerospace to further develop future fighter concepts. The contract stipulates that Saab will submit design drawings for a demonstrator, not a fully operational prototype, by the end of 2025. This demonstrator is expected to provide important data for developing a new combat aircraft system. Saab is also conducting research into advanced materials, artificial intelligence, and stealth or low observability technologies, with contributions from the FMV, Swedish Armed Forces, and GKN Aerospace.

This agreement, running from 2024 to 2025 with potential extensions, involves evaluating both existing and new technologies and conducting demonstrations with a range of national and international stakeholders. GKN Aerospace, drawing on its experience with the RM12 and RM16 engines for the JAS 39 Gripen series, has signed a new cooperation agreement with Saab to investigate innovative solutions for future fighter systems. Additionally, GKN Aerospace’s center in Trollhättan, Sweden, has received a €59.5 million investment to expand its additive fabrication technology capabilities, aiming to advance industrialization, reduce environmental impact, and meet future power and propulsion requirements.

Saab is also conducting research into advanced materials, artificial intelligence, and stealth or low observability technologies, with contributions from the FMV, Swedish Armed Forces, and GKN Aerospace. (Picture source: Saab)

These activities reflect ongoing efforts by Saab and GKN Aerospace to address Sweden’s defense needs through the exploration of new technologies and strategic partnerships. Saab has called for a decision on the new fighter system to be made before 2030, warning that delays could affect Sweden’s capacity to respond to technological changes and developments in the defense sector. In this context, the Swedish Armed Forces have started the process of identifying a future combat aircraft system to replace the Jas Gripen, which is expected to remain in service until 2050-2060. A decision is anticipated around 2030, with Sweden considering whether to develop its own combat aircraft, collaborate with other nations, or purchase an existing model from a foreign supplier.

The decision on which path to take involves weighing various factors, including national defense needs, employment, and Sweden’s position as a technologically advanced nation. Three options are under consideration: developing a new aircraft domestically, partnering with other countries for joint development, or purchasing an existing fighter aircraft. Each of these options comes with different implications. There are differing views among experts on the viability of continuing with a national development approach. Lars Peder Haga, a researcher at the Norwegian Defense Academy, expressed skepticism about Sweden pursuing another independent project, citing the rarity and high costs of developing fighter jets independently. Tomi Lyytinen, a lieutenant colonel and air combat instructor at the Finnish Defense Academy, also believes it would be financially unfeasible for Sweden to independently develop a sixth-generation combat aircraft.

Historical cases illustrate the challenges associated with these concerns. During the 1960s, the development of the Viggen aircraft presented Sweden with considerable financial challenges. More recently, the United Kingdom estimated that developing its next-generation fighter would cost over €14 billion, with additional contributions from partner countries such as Italy and Japan. Although Sweden has been recognized for efficiency in defense projects, the costs of developing a new Swedish fighter aircraft could still be high, according to Anders Foyer, deputy project manager at FOI, the Total Defense Research Institute. Foyer’s team is currently analyzing the total life-cycle cost of the Gripen and comparing it with potential alternatives.

During the 1960s, the development of the Viggen aircraft presented Sweden with considerable financial challenges. (Picture source: Planespotters.net/Daniel Schwinn)

Complicating the decision further, all of Sweden’s NATO neighbors—Finland, Denmark, and Norway—have opted to purchase the American F-35 fighter aircraft, which has involved substantial costs. For instance, Norway’s estimated life-cycle costs for the F-35 were initially set at approximately €28.9 billion, although this figure has been questioned by the Norwegian National Audit Office. A decision to purchase foreign aircraft could have significant implications for Saab, particularly for its aviation division in Linköping, where 6,000 employees work. This potential impact is an important factor, as the decision is influenced not only by military needs but also by broader societal and industrial considerations, as noted by Karl Engelbrektson, a major general and former head of the Swedish Army.

Engelbrektson cautioned that an entirely new Swedish development project could be so costly that it might limit other critical defense investments. He suggested that exploring credible international partnerships might be a more viable path forward, a view supported by Lyytinen, who indicated that Sweden appears to be moving toward some form of international cooperation, potentially within a European or Euro-Japanese framework. At present, two major European fighter programs are underway. Sweden initially participated in preliminary work for the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), which involves the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan. However, Swedish Defense Minister Pål Jonson recently stated that GCAP no longer aligns with Sweden’s timeline or strategic requirements. Another significant program, the Franco-German-Spanish Future Combat Air System (FCAS), has not generated substantial interest from Sweden.

All of Sweden’s NATO neighbors (Finland, Denmark, and Norway) have opted to purchase the American F-35 Lightning II stealth fighter aircraft, which has involved substantial costs. (Picture source: US DoD)

These programs are part of broader initiatives among NATO countries to develop sixth-generation fighter jets with enhanced capabilities, such as stealth technology and drone integration. The GCAP project involves approximately 9,000 personnel, while the FCAS initiative is a collaborative effort between France, Spain, and Germany, with Belgium also potentially participating. Meanwhile, the United States is working on its Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program, although this has faced delays due to cost concerns.

As Sweden evaluates its options, discussions are increasingly focusing on the potential incorporation of autonomous capabilities into future combat aircraft. Concepts under consideration include smaller unmanned vehicles that could assist piloted aircraft or larger, fully unmanned combat systems. These systems would operate within a network of sensors connecting satellites, ships, and other military assets, allowing for rapid information sharing and coordinated responses to threats. While the path Sweden will ultimately choose remains uncertain, Defense Minister Pål Jonson has indicated that international cooperation will be necessary, though the form it will take has yet to be determined.

The Swedish Armed Forces have started the process of identifying a future combat aircraft system to replace the Jas Gripen, which is expected to remain in service until 2050-2060. (Picture source: Airliners.net/Oleg V. Belyakov)

{loadposition bannertop}

{loadposition sidebarpub}

On August 24, 2024, in an interview with Dagens Nyheter, Peter Nilsson, Saab’s Head of Advanced Programs, announced that Saab is advancing its development of both manned and unmanned fighter concepts as part of efforts to establish a sixth-generation combat air platform for the Swedish Armed Forces. Nilsson provided details on Saab’s ongoing exploration of future fighter options on behalf of the Swedish government, presenting the company as a candidate for developing Sweden’s next combat aircraft.

Follow Army Recognition on Google News at this link

Saab is working on both manned and unmanned fighters as part of efforts to establish a sixth-generation combat air platform for the Swedish Armed Forces. (Picture source: Saab)

Nilsson argued that conditions are currently favorable for Saab to build a new combat aircraft for Sweden, citing the availability of a trained workforce, the use of modern digital engineering techniques, and experience gained from recent projects such as the Gripen E fighter, the GlobalEye surveillance aircraft, and the T-7A trainer aircraft. He addressed concerns about the costs associated with developing a new fighter aircraft domestically, suggesting that these concerns may be misplaced. He referenced the development of the JAS 39 Gripen in the 1980s, when similar doubts were raised but ultimately overcome.

Sweden’s development of turbojet-powered combat aircraft began with the Saab 21R, a jet adaptation of the earlier piston-engine Saab 21, which first flew in 1947 as Sweden’s initial jet aircraft. This was succeeded by the Saab 29 Tunnan in the early 1950s, featuring a swept-wing design and capable of achieving supersonic speed in a shallow dive. The Saab 32 Lansen, which entered service in the mid-1950s, was designed for various roles, including attack, reconnaissance, and maritime patrol.

The Saab 35 Draken, operational from 1960, utilized a double-delta wing design and incorporated canard foreplanes to enhance performance. The Saab 37 Viggen, introduced in the early 1970s, included modern avionics, an afterburning engine, and a thrust-reversing capability, supporting both air defense and ground attack functions. This progression led to the Saab JAS 39 Gripen, which entered service in the 1990s as a multirole fighter with updated avionics, fly-by-wire controls, and a modular structure designed to fulfill various military roles.

The Saab 29 Tunnan was launched in the early 1950s as the first post-WWII Western European fighter to be produced with a swept-wing design. (Picture source: Flickr/Ragnhild & Neil Crawford)

Nilsson suggested that a similar approach to the development of the Gripen could be effective for a new fighter aircraft. This strategy involved collaborating with multiple international partners while maintaining control over the design process within Sweden. He noted that the Gripen E, while primarily developed by Saab, includes a significant proportion of components from foreign suppliers, with Saab integrating these into a single system. This model could potentially be applied to future projects, balancing local oversight with international collaboration.

As part of these efforts, the Swedish Defence Materiel Administration (FMV) signed a contract earlier this year with Saab and GKN Aerospace to further develop future fighter concepts. The contract stipulates that Saab will submit design drawings for a demonstrator, not a fully operational prototype, by the end of 2025. This demonstrator is expected to provide important data for developing a new combat aircraft system. Saab is also conducting research into advanced materials, artificial intelligence, and stealth or low observability technologies, with contributions from the FMV, Swedish Armed Forces, and GKN Aerospace.

This agreement, running from 2024 to 2025 with potential extensions, involves evaluating both existing and new technologies and conducting demonstrations with a range of national and international stakeholders. GKN Aerospace, drawing on its experience with the RM12 and RM16 engines for the JAS 39 Gripen series, has signed a new cooperation agreement with Saab to investigate innovative solutions for future fighter systems. Additionally, GKN Aerospace’s center in Trollhättan, Sweden, has received a €59.5 million investment to expand its additive fabrication technology capabilities, aiming to advance industrialization, reduce environmental impact, and meet future power and propulsion requirements.

Saab is also conducting research into advanced materials, artificial intelligence, and stealth or low observability technologies, with contributions from the FMV, Swedish Armed Forces, and GKN Aerospace. (Picture source: Saab)

These activities reflect ongoing efforts by Saab and GKN Aerospace to address Sweden’s defense needs through the exploration of new technologies and strategic partnerships. Saab has called for a decision on the new fighter system to be made before 2030, warning that delays could affect Sweden’s capacity to respond to technological changes and developments in the defense sector. In this context, the Swedish Armed Forces have started the process of identifying a future combat aircraft system to replace the Jas Gripen, which is expected to remain in service until 2050-2060. A decision is anticipated around 2030, with Sweden considering whether to develop its own combat aircraft, collaborate with other nations, or purchase an existing model from a foreign supplier.

The decision on which path to take involves weighing various factors, including national defense needs, employment, and Sweden’s position as a technologically advanced nation. Three options are under consideration: developing a new aircraft domestically, partnering with other countries for joint development, or purchasing an existing fighter aircraft. Each of these options comes with different implications. There are differing views among experts on the viability of continuing with a national development approach. Lars Peder Haga, a researcher at the Norwegian Defense Academy, expressed skepticism about Sweden pursuing another independent project, citing the rarity and high costs of developing fighter jets independently. Tomi Lyytinen, a lieutenant colonel and air combat instructor at the Finnish Defense Academy, also believes it would be financially unfeasible for Sweden to independently develop a sixth-generation combat aircraft.

Historical cases illustrate the challenges associated with these concerns. During the 1960s, the development of the Viggen aircraft presented Sweden with considerable financial challenges. More recently, the United Kingdom estimated that developing its next-generation fighter would cost over €14 billion, with additional contributions from partner countries such as Italy and Japan. Although Sweden has been recognized for efficiency in defense projects, the costs of developing a new Swedish fighter aircraft could still be high, according to Anders Foyer, deputy project manager at FOI, the Total Defense Research Institute. Foyer’s team is currently analyzing the total life-cycle cost of the Gripen and comparing it with potential alternatives.

During the 1960s, the development of the Viggen aircraft presented Sweden with considerable financial challenges. (Picture source: Planespotters.net/Daniel Schwinn)

Complicating the decision further, all of Sweden’s NATO neighbors—Finland, Denmark, and Norway—have opted to purchase the American F-35 fighter aircraft, which has involved substantial costs. For instance, Norway’s estimated life-cycle costs for the F-35 were initially set at approximately €28.9 billion, although this figure has been questioned by the Norwegian National Audit Office. A decision to purchase foreign aircraft could have significant implications for Saab, particularly for its aviation division in Linköping, where 6,000 employees work. This potential impact is an important factor, as the decision is influenced not only by military needs but also by broader societal and industrial considerations, as noted by Karl Engelbrektson, a major general and former head of the Swedish Army.

Engelbrektson cautioned that an entirely new Swedish development project could be so costly that it might limit other critical defense investments. He suggested that exploring credible international partnerships might be a more viable path forward, a view supported by Lyytinen, who indicated that Sweden appears to be moving toward some form of international cooperation, potentially within a European or Euro-Japanese framework. At present, two major European fighter programs are underway. Sweden initially participated in preliminary work for the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), which involves the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan. However, Swedish Defense Minister Pål Jonson recently stated that GCAP no longer aligns with Sweden’s timeline or strategic requirements. Another significant program, the Franco-German-Spanish Future Combat Air System (FCAS), has not generated substantial interest from Sweden.

All of Sweden’s NATO neighbors (Finland, Denmark, and Norway) have opted to purchase the American F-35 Lightning II stealth fighter aircraft, which has involved substantial costs. (Picture source: US DoD)

These programs are part of broader initiatives among NATO countries to develop sixth-generation fighter jets with enhanced capabilities, such as stealth technology and drone integration. The GCAP project involves approximately 9,000 personnel, while the FCAS initiative is a collaborative effort between France, Spain, and Germany, with Belgium also potentially participating. Meanwhile, the United States is working on its Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program, although this has faced delays due to cost concerns.

As Sweden evaluates its options, discussions are increasingly focusing on the potential incorporation of autonomous capabilities into future combat aircraft. Concepts under consideration include smaller unmanned vehicles that could assist piloted aircraft or larger, fully unmanned combat systems. These systems would operate within a network of sensors connecting satellites, ships, and other military assets, allowing for rapid information sharing and coordinated responses to threats. While the path Sweden will ultimately choose remains uncertain, Defense Minister Pål Jonson has indicated that international cooperation will be necessary, though the form it will take has yet to be determined.

The Swedish Armed Forces have started the process of identifying a future combat aircraft system to replace the Jas Gripen, which is expected to remain in service until 2050-2060. (Picture source: Airliners.net/Oleg V. Belyakov)