Venezuela Turns to Russia for Ballistic Missiles Able to Target U.S. Assets if Crisis Grows

{loadposition bannertop}

{loadposition sidebarpub}

A senior Russian lawmaker said Moscow is ready to supply advanced Oreshnik ballistic and Kalibr cruise missiles to Venezuela. The move would mark a major escalation in Russian support for Caracas and create new challenges for U.S. regional defense planning.

According to information disclosed by Gazeta.ru, on November 1, 2025, senior Russian lawmaker Alexei Zhuravlyov said Moscow is already supplying weapons to Venezuela and sees no obstacle to transferring the new Oreshnik ballistic missile or Kalibr cruise missiles to Caracas. The remarks came as Venezuelan officials publicly sought military assistance from Russia, China, and Iran against what they describe as mounting U.S. pressure and rumors of a possible operation. Gazeta.ru is not an independent journal; the purpose of the article is to analyze what capabilities Venezuela would have if such missiles were transferred by Russia.Follow Army Recognition on Google News at this link

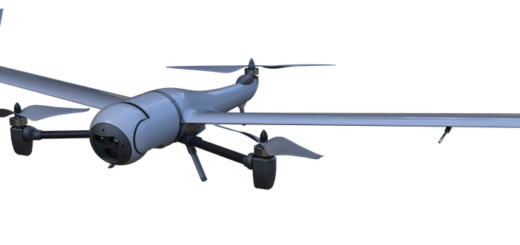

Russia’s new Oreshnik ballistic missile and Kalibr cruise missiles could soon reach Venezuela, a move that would extend Moscow’s strike reach into the Western Hemisphere and challenge U.S. dominance in the Caribbean as tensions rise between Washington and Caracas (Picture source: Army Recognition Edit/ Vitaly Kuzmin).

Ukrainian and Western reporting over the last year has treated Oreshnik as a road-mobile, intermediate-range ballistic missile derived from the RS-26 line, with claimed top speeds near Mach 10 and a notional reach up to roughly 5,000 kilometers. Washington first labeled the missile an intermediate-range system after a November 2024 strike on Dnipro, while subsequent coverage added that it can carry multiple reentry vehicles. In his interview, Zhuravlyov went further, calling the system a “new development” that Russia could ship to a “friendly” country such as Venezuela.

The Kalibr family presents a different kind of problem. Russian domestic land-attack variants have been credited with ranges in the 1,500 to 2,500 kilometer class, while export “E” versions are typically held near 300 kilometers under Missile Technology Control Regime guidelines. Containerized Club-K launchers, which house four cruise missiles inside a standard 20- or 40-foot shipping container, provide a deceptive and easily relocatable firing unit that can ride trucks, railcars, or merchant ships.

Why Caracas wants these systems is straightforward: Venezuela has long sought an offset to U.S. conventional overmatch and episodic displays of force in the Caribbean. In recent weeks, Washington surged naval and air assets, including a carrier group and bomber demonstrations near Venezuelan airspace, as part of an expanded anti-narcotics campaign. The Pentagon’s moves have triggered Venezuelan mobilizations and sharpened rhetoric on both sides, with President Nicolás Maduro publicly signaling “maximum preparedness.”

Oreshnik missiles would give Caracas a theater-level coercive instrument. The missile’s road mobility allows dispersal on transporter-erector-launchers under canopy, quick occupation of pre-surveyed hides, and shoot-and-scoot tactics that compress U.S. warning timelines. If based in northern Venezuela, even a token battery would force U.S. Northern and Southern Commands to allocate more Aegis ballistic missile defense ships and persistent ISR to track TELs and cue interceptors. The system’s reported multi-warhead configuration and high reentry speed would further burden any point defense protecting Florida or Puerto Rico. None of this makes a first strike likely from Caracas, but the political utility of simply fielding the option is obvious.

Kalibr would fill the other half of the deterrent picture. A shore-based or containerized launcher network could threaten forward operating locations and naval units within a 300-kilometer export envelope, while covert maritime deployment aboard state-controlled merchant hulls could compress distance and surprise planners. Low-altitude subsonic cruise profiles exploit coastal clutter and make detection a race for airborne early warning and joint fires cells. In practical terms, Caracas would be wagering that even a limited Kalibr presence raises U.S. escalation costs enough to deter strikes on Venezuelan soil.

In a signaling phase, Venezuela would likely conduct publicized dispersals of missile units and selective imagery releases while staging a measured Kalibr test into a closed box at sea. If a crisis deepened, the next rung could be a preemptive salvo at a forward fuel farm or pier complex supporting U.S. operations in Puerto Rico, paired with Oreshnik alerts that force U.S. BMD repositioning. The highest-risk rung would be any ballistic shot toward U.S. territory, an act that would invite overwhelming retaliation and is therefore more valuable to Caracas as a threat than as an action.

Countermeasures exist, but they would strain bandwidth. The United States could surge Aegis BMD destroyers to the Caribbean, deploy additional airborne ISR for TEL hunting, and harden high-value nodes with layered defenses. Yet each ship pulled south is a ship not available for Europe or the Indo-Pacific. Cruise-missile defense around coastal bases depends on alert airborne sensors and local SHORAD, both of which are intensive when sustained. The doctrinal answer would be persistent find-fix-finish against Venezuelan launchers, a campaign that rarely stays tidy once dispersal begins.

Legally and diplomatically, any transfer would collide with MTCR norms. The regime urges partners to deny exports of Category I systems capable of delivering at least a 500-kilogram payload to at least 300 kilometers, which would capture Oreshnik outright and put strict restraints on long-range Kalibr models. Russia is a partner, but the MTCR is an informal arrangement rather than a treaty, and Moscow routinely frames transfers as sovereign decisions in response to U.S. actions. Expect Russia to argue that export-restricted Kalibr versions respect the letter of MTCR while blaming Washington for escalation.

The Russia-Venezuela defense link gives this threat credibility. Caracas purchased 24 Su-30MK2 multirole fighters starting in 2006 and later fielded a long-range air defense architecture anchored by S-300VM Antey-2500, with medium-range Buk-M2E and point-defense Pantsir-S1 complementing the outer ring. Open reporting and industry sources show Buk-M2E deliveries in the 2013 to 2015 period, while S-300VM first appeared publicly in Venezuela in 2013 after deliveries that independent trackers place around 2012. The inventory has been sustained unevenly since, yet recent Russian Il-76 flights into Caracas suggest renewed logistics pipelines and training packages.

Moving Oreshnik or Kalibr into Venezuela would be a strong message: containerized cruise-missile launchers are the easiest to preposition discretely by sea or air, making Club-K the most plausible near-term option. A road-mobile IRBM battery requires trained crews, protected hides, specialized fuel and test equipment, and integration into a national command chain that can withstand cyber and kinetic pressure. Recent flight-tracking of a Russian Il-76 with sanctions-tangled ownership reaching Caracas offers a glimpse of how Moscow could stage early deliveries, while heavier missile systems would likely demand multi-sortie air bridges or sealift.

To ground this discussion, it helps to be precise about the missiles themselves. Oreshnik, as described by Russian and Western sources, is an intermediate-range, road-mobile ballistic missile reportedly derived from RS-26, capable of very high terminal speeds and multiple reentry vehicles. Russian officials have hinted at entry into service in 2025 and even forward deployment to Belarus. Kalibr’s 3M-14 land-attack line uses a solid-fuel booster and turbojet sustainer, cruises around Mach 0.8 to 0.9, and carries a warhead in the 400 to 500 kilogram class. Domestic ranges stretch beyond 1,500 kilometers, while export 3M-14E variants are commonly cited at 300 kilometers.

The stakes for Washington are real: a credible Oreshnik presence in Venezuela would force persistent Aegis coverage in the Caribbean and a round-the-clock hunt for TELs, while even a limited Kalibr footprint would make every pier, pump, and ammunition site in Puerto Rico a harder target to defend. Kyiv-based outlets that first amplified Zhuravlyov’s comments also highlight the expanding U.S. footprint, a narrative Moscow will exploit as it tests how far it can go without triggering a red line. The danger is less a bolt-from-the-blue strike than a gradual normalization of Russian long-range strike infrastructure on U.S. near seas.

Venezuela’s ability to operate complex missile systems under sanctions and economic stress is not assured, and Russian claims about Oreshnik’s performance remain only partially verified by open sources. But the political logic is plain: by dangling Oreshnik and Kalibr, Moscow reassures a partner, advertises capability, and forces U.S. planners to spend time, ships, and ISR cycles on a new front.

{loadposition bannertop}

{loadposition sidebarpub}

A senior Russian lawmaker said Moscow is ready to supply advanced Oreshnik ballistic and Kalibr cruise missiles to Venezuela. The move would mark a major escalation in Russian support for Caracas and create new challenges for U.S. regional defense planning.

According to information disclosed by Gazeta.ru, on November 1, 2025, senior Russian lawmaker Alexei Zhuravlyov said Moscow is already supplying weapons to Venezuela and sees no obstacle to transferring the new Oreshnik ballistic missile or Kalibr cruise missiles to Caracas. The remarks came as Venezuelan officials publicly sought military assistance from Russia, China, and Iran against what they describe as mounting U.S. pressure and rumors of a possible operation. Gazeta.ru is not an independent journal; the purpose of the article is to analyze what capabilities Venezuela would have if such missiles were transferred by Russia.

Follow Army Recognition on Google News at this link

Russia’s new Oreshnik ballistic missile and Kalibr cruise missiles could soon reach Venezuela, a move that would extend Moscow’s strike reach into the Western Hemisphere and challenge U.S. dominance in the Caribbean as tensions rise between Washington and Caracas (Picture source: Army Recognition Edit/ Vitaly Kuzmin).

Ukrainian and Western reporting over the last year has treated Oreshnik as a road-mobile, intermediate-range ballistic missile derived from the RS-26 line, with claimed top speeds near Mach 10 and a notional reach up to roughly 5,000 kilometers. Washington first labeled the missile an intermediate-range system after a November 2024 strike on Dnipro, while subsequent coverage added that it can carry multiple reentry vehicles. In his interview, Zhuravlyov went further, calling the system a “new development” that Russia could ship to a “friendly” country such as Venezuela.

The Kalibr family presents a different kind of problem. Russian domestic land-attack variants have been credited with ranges in the 1,500 to 2,500 kilometer class, while export “E” versions are typically held near 300 kilometers under Missile Technology Control Regime guidelines. Containerized Club-K launchers, which house four cruise missiles inside a standard 20- or 40-foot shipping container, provide a deceptive and easily relocatable firing unit that can ride trucks, railcars, or merchant ships.

Why Caracas wants these systems is straightforward: Venezuela has long sought an offset to U.S. conventional overmatch and episodic displays of force in the Caribbean. In recent weeks, Washington surged naval and air assets, including a carrier group and bomber demonstrations near Venezuelan airspace, as part of an expanded anti-narcotics campaign. The Pentagon’s moves have triggered Venezuelan mobilizations and sharpened rhetoric on both sides, with President Nicolás Maduro publicly signaling “maximum preparedness.”

Oreshnik missiles would give Caracas a theater-level coercive instrument. The missile’s road mobility allows dispersal on transporter-erector-launchers under canopy, quick occupation of pre-surveyed hides, and shoot-and-scoot tactics that compress U.S. warning timelines. If based in northern Venezuela, even a token battery would force U.S. Northern and Southern Commands to allocate more Aegis ballistic missile defense ships and persistent ISR to track TELs and cue interceptors. The system’s reported multi-warhead configuration and high reentry speed would further burden any point defense protecting Florida or Puerto Rico. None of this makes a first strike likely from Caracas, but the political utility of simply fielding the option is obvious.

Kalibr would fill the other half of the deterrent picture. A shore-based or containerized launcher network could threaten forward operating locations and naval units within a 300-kilometer export envelope, while covert maritime deployment aboard state-controlled merchant hulls could compress distance and surprise planners. Low-altitude subsonic cruise profiles exploit coastal clutter and make detection a race for airborne early warning and joint fires cells. In practical terms, Caracas would be wagering that even a limited Kalibr presence raises U.S. escalation costs enough to deter strikes on Venezuelan soil.

In a signaling phase, Venezuela would likely conduct publicized dispersals of missile units and selective imagery releases while staging a measured Kalibr test into a closed box at sea. If a crisis deepened, the next rung could be a preemptive salvo at a forward fuel farm or pier complex supporting U.S. operations in Puerto Rico, paired with Oreshnik alerts that force U.S. BMD repositioning. The highest-risk rung would be any ballistic shot toward U.S. territory, an act that would invite overwhelming retaliation and is therefore more valuable to Caracas as a threat than as an action.

Countermeasures exist, but they would strain bandwidth. The United States could surge Aegis BMD destroyers to the Caribbean, deploy additional airborne ISR for TEL hunting, and harden high-value nodes with layered defenses. Yet each ship pulled south is a ship not available for Europe or the Indo-Pacific. Cruise-missile defense around coastal bases depends on alert airborne sensors and local SHORAD, both of which are intensive when sustained. The doctrinal answer would be persistent find-fix-finish against Venezuelan launchers, a campaign that rarely stays tidy once dispersal begins.

Legally and diplomatically, any transfer would collide with MTCR norms. The regime urges partners to deny exports of Category I systems capable of delivering at least a 500-kilogram payload to at least 300 kilometers, which would capture Oreshnik outright and put strict restraints on long-range Kalibr models. Russia is a partner, but the MTCR is an informal arrangement rather than a treaty, and Moscow routinely frames transfers as sovereign decisions in response to U.S. actions. Expect Russia to argue that export-restricted Kalibr versions respect the letter of MTCR while blaming Washington for escalation.

The Russia-Venezuela defense link gives this threat credibility. Caracas purchased 24 Su-30MK2 multirole fighters starting in 2006 and later fielded a long-range air defense architecture anchored by S-300VM Antey-2500, with medium-range Buk-M2E and point-defense Pantsir-S1 complementing the outer ring. Open reporting and industry sources show Buk-M2E deliveries in the 2013 to 2015 period, while S-300VM first appeared publicly in Venezuela in 2013 after deliveries that independent trackers place around 2012. The inventory has been sustained unevenly since, yet recent Russian Il-76 flights into Caracas suggest renewed logistics pipelines and training packages.

Moving Oreshnik or Kalibr into Venezuela would be a strong message: containerized cruise-missile launchers are the easiest to preposition discretely by sea or air, making Club-K the most plausible near-term option. A road-mobile IRBM battery requires trained crews, protected hides, specialized fuel and test equipment, and integration into a national command chain that can withstand cyber and kinetic pressure. Recent flight-tracking of a Russian Il-76 with sanctions-tangled ownership reaching Caracas offers a glimpse of how Moscow could stage early deliveries, while heavier missile systems would likely demand multi-sortie air bridges or sealift.

To ground this discussion, it helps to be precise about the missiles themselves. Oreshnik, as described by Russian and Western sources, is an intermediate-range, road-mobile ballistic missile reportedly derived from RS-26, capable of very high terminal speeds and multiple reentry vehicles. Russian officials have hinted at entry into service in 2025 and even forward deployment to Belarus. Kalibr’s 3M-14 land-attack line uses a solid-fuel booster and turbojet sustainer, cruises around Mach 0.8 to 0.9, and carries a warhead in the 400 to 500 kilogram class. Domestic ranges stretch beyond 1,500 kilometers, while export 3M-14E variants are commonly cited at 300 kilometers.

The stakes for Washington are real: a credible Oreshnik presence in Venezuela would force persistent Aegis coverage in the Caribbean and a round-the-clock hunt for TELs, while even a limited Kalibr footprint would make every pier, pump, and ammunition site in Puerto Rico a harder target to defend. Kyiv-based outlets that first amplified Zhuravlyov’s comments also highlight the expanding U.S. footprint, a narrative Moscow will exploit as it tests how far it can go without triggering a red line. The danger is less a bolt-from-the-blue strike than a gradual normalization of Russian long-range strike infrastructure on U.S. near seas.

Venezuela’s ability to operate complex missile systems under sanctions and economic stress is not assured, and Russian claims about Oreshnik’s performance remain only partially verified by open sources. But the political logic is plain: by dangling Oreshnik and Kalibr, Moscow reassures a partner, advertises capability, and forces U.S. planners to spend time, ships, and ISR cycles on a new front.